A brush with death

Orhan Pamuk's My Name is Red

Orhan Pamuk's My Name is RedAbout suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters; how well, they understood

Its human position;

- W. H. Auden

There is a scene in Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name is Red, where the Sultan orders the three great miniaturists of his court to each paint a horse. As they compete, one master says that when he paints a horse he becomes a horse; a second says that when he paints a horse he becomes one of the Great Masters painting a horse, the third affirms that when he paints a horse he remains himself.

It is this multiplicity of perspectives, of approaches to art, that My Name is Red is a celebration of. The setting is Istanbul, the world of the Turkish miniaturists, who sit in their workshops decorating great and holy books for the pleasure and prestige of their rulers. Faithful imitation is the creed of these painters, their greatest joy is to render each image in a way that makes it indistinguishable from all other similar illustrations, so that the image itself becomes absolute, timeless. For these painters, individuality, or ‘style’, is error.

Into the rigidity of this world comes a vision of painting, imported from the West, where the great Italian painters are discovering depth and light and perspective, and are beginning to paint portraits of shocking and lifelike glory. Such a technique is not simply antithetical to the art of the Turks, it is also potentially blasphemous, since the creation of idols or portraits is forbidden by Islam.

Nevertheless, the Sultan orders the creation of a secret and glorious book that endeavours to adopt this new form of painting – a project that causes grave rifts in the fraternity of the miniaturists and ultimately ends in a series of gruesome murders.

Nevertheless, the Sultan orders the creation of a secret and glorious book that endeavours to adopt this new form of painting – a project that causes grave rifts in the fraternity of the miniaturists and ultimately ends in a series of gruesome murders.Pamuk uses this setting to indulge in a long and insightful meditation on the nature of art and through it, the deeper meaning of existence. At the heart of the questions that the book raises is the debate between the universal and the particular, and their respective places in the creative arts. If Art is not to be universal, the old Masters ask, if it is to celebrate nothing more magical than the ordinary and the human, if it is not to improve on reality in any way, then what is the point of it? But what does Art mean if it is completely divorced from the real world, the supporters of the new style respond, how can a man who has never seen a battle paint one? As a discussion about realism vs idealism in art this is an interesting discussion by itself, but in Pamuk’s hand it becomes an allegory for an even deeper question – what is the meaning of the self? Does virtue lie in celebrating the self or effacing it? Does greatness consist of losing oneself in the infinite, or in setting one’s self apart from it? This is not simply a clash of two artistic traditions, it is the fundamental battle of generations, the eternal conflict between new ideas and the old traditions.

Pamuk’s answer to this debate, which he places, subtly and ironically, in the mouth of the Master of the Miniaturists himself, is that both sides of the debate are right. Virtue and greatness consist not in stagnating in the name of the old but in drawing on what one can learn from the old masters to create a new tradition of one’s own. This is the true challenge for the artist. It is, moreover, a difficult challenge – one that can easily destroy even the most talented of creative spirits, one that must not be undertaken lightly.

But there is much more to My Name is Red than this. As these ideas play themselves out in the background, the foreground is taken up by one of the more exciting murder mysteries I have read this year. As the novel opens, a miniaturist has been murdered, done in by one of his brethren, and the plot of the novel is essentially a breathless race to find and apprehend this murderer. At the centre of this investigation is Black, a young man who returns to Istanbul after an exile of 12 years, only to find himself plunged into a world of art and intrigue. As a character, Black in the quintessential Hitchcock hero – a well-meaning but unimpressive young man, who finds himself trapped in a ruthless endgame where he must solve a terrible mystery while also somehow managing to secure the hand of his beloved. Blending suspense and romance, the plot of My Name is Red is as engaging as it is dramatic, filled with colourful characters, humorous asides and some truly enchanting story-telling. As the novel builds towards its climax, the tension is almost nerve-wrenching and you can feel yourself almost screaming at Pamuk to get on with it.

This is both one of the glories of the book and one of its deepest failures. On the one hand, by interspersing long, sombre meditations on art with some fast-paced action, Pamuk brilliantly counterpoints the universal with the human, embellishing the point of his book, and considerably enriching it as a novel. On the other hand, large parts of the novel seem to go on for too long, with Pamuk making the same point again and again, long after one has already understood what he is trying to say. I suspect the repetition is part of Pamuk’s design – his attempt to demonstrate why the slower, more meandering ways of the old ones would be difficult to accept for those of us who live in this more impatient, urgent age, but it gets to the point where it’s almost wearying, so that you’re tempted to simply skip ahead a few pages and get on with the action. It may well be the fault of the translation that Pamuk is unable to maintain the pace of the book, but it is undeniable that there are points where this book flags.

That said, this is still a wickedly intelligent book. It’s not just that the plot sets up the universal debate about art versus the deeply human concerns of Black and his beloved, it’s also the way Pamuk uses the central idea of miniaturist art, the denial of personal style, as the key to his murder mystery. Even though all three suspects take on the role of narrator at different points in the novel, their identities remain distinguished in only the most subtle ways – given how Pamuk portrays them, they are hard to tell apart. It is this that makes it difficult to identify the murderer among them, not only for Black but for the reader as well. Thus Pamuk manages to use a way of looking at art as the tool by which he creates suspense in his novel – a truly brilliant achievement.

My Name is Red is a fascinating read – not least because of Pamuk’s clever, innovative style. Pamuk reads like a combination of Rushdie and Mahfouz - a restless inventor joined to a writer of melancholy and thoughtful prose. The novel shifts perspective endlessly - it is told through the eyes of each one of the key characters, as well as from the perspectives of various paintings and objects, and a few corpses along the way. Fables, legends and myths adorn the writing at every turn, there are numerous short stories sprinkled through the book that would do Borges proud. In the final analysis, if you come away less stunned by the brilliance of the writing than you should be, it could only be because of the baroque nature of Pamuk’s ornamentation, the sheer denseness of his work that sits heavy on the mind, like a rich halva.

Bottomline: My Name is Red is that rare thing: a novel that manages to be both thought-provoking and entertaining, a deeply allegorical murder mystery. If it feels a trifle long and stifling at times, it is only because our palates are not used to prose that is so densely, richly beautiful.

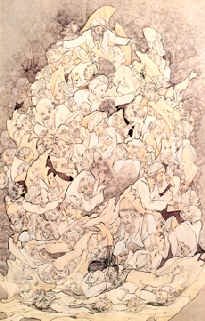

P.S. The two paintings in the middle: the one on the left is a painting of a musician by the great Persian miniaturist Behzad, the one on the right is a painting of Orpheus (modelled on one of the Medicis) by Bronzino. You can see the difference.

1 Comments:

Pamuk is next in line, I'm in fact waiting to read him. Right now I'm in the middle of 'Memories of my Melancholy Whores'.

Post a Comment

<< Home